Was Silvio Berlusconi’s rise to power founded on an “original sin” — a secret deal between politicians and the Mafia to stop its violence in exchange for political protection?

That explosive question is at the center of a trial under way in Palermo that observers hope will shed light on one of the murkiest and most tumultuous periods in recent Italian history.

The court is considering whether leading politicians and police officials negotiated with Sicilian Mafia bosses to end a wave of bombings in the early 1990s in return for favors.

Then, prosecutors allege, the dons of Italy’s most notorious mafia put aside their feuds and vendettas and agreed to wage war on the Italian government, effectively blackmailing the Italian state to submit to their will.

“The escalation of violence in 1992 and 1993 was aimed at pushing the state to come to a common understanding with the Sicilian Mafia,” wrote sociologist Alessandra Dino in the 2006 book “The Mafia and Anti-Mafia Dictionary.” “The violence was aimed at causing a political turnover.”

Although Berlusconi isn’t on trial, some believe the media billionaire benefited from the actions of his associates by taking power after the bombings and a series of corruption scandals brought down the old political establishment.

Historians believe the Cosa Nostra killed 40 people as part of its campaign between 1988 and 1992. The violence claimed the lives of some of Italy’s top anti-Mafia judges, along with their family members, staff members and friends.

Among the victims was judge Giovanni Falcone, who was blown up by a highway bomb near Palermo in 1992 along with his wife and three bodyguards. Two months later, another blast in Palermo claimed the life of Falcone’s close friend, prosecutor Paolo Borsellino, and his five guards.

The attacks also killed politicians and ordinary people and caused chaos in daily life as bombs went off in streets and public squares.

“The whole country was on its knees, we were just expecting a final shot in the head,” Turin prosecutor Giancarlo Caselli says to the author. “We were an inch from becoming a narco- or mafia-state.”

A report by Palermo prosecutors claims that politicians and Mafia bosses held a series of secret meetings in 1992 and 1993 to end the violence before finally concluding an agreement in 1994.

They say officials initiated the pact, in which police promised to soften some anti-Mafia laws and ease prison regulations for convicted gangsters.

Among those on trial is Sicily’s former “boss of the bosses,” Toto Riina, his successor Bernardo Provenzano and three other dons. They’re accused of violence or threats against the state.

Prosecutors have also charged former government minister Calogero Mannino and former senator Marcello Dell’Utri, Berlusconi’s close associate who’s alleged to have brokered the deal. Three former police generals are accused of violence against the state and former senate president Nicola Mancino faces a count of false testimony.

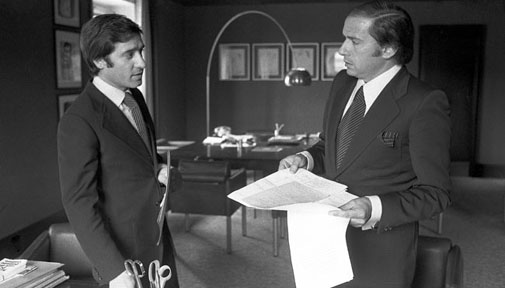

Young Silvio Berlusconi (right) and Marcello Dell’Utri (left). Photo: terza-pagina.it

“They are all charged with acting deliberately so that the threat [could] be successfully put in place, [and] functioning as conscious mediators between the Mafia and the threatened party,” the indictment reads.

Dell’Utri helped Berlusconi found his first political vehicle, Forza Italia, in 1993. The new conservative party soon stormed to the top of the polls just as Italy’s older parties were discredited thanks to corruption and Mafia scandals.

Those were troubled years for Italy: A mammoth nationwide judicial investigation called Mani Pulite, clean hands, prompted the political system’s effective collapse. Several politicians and business leaders committed suicide after their crimes were made public. Others fled abroad.

The turmoil set the stage for Berlusconi. Il Cavaliere — the knight, as he’s nicknamed — played the role of savior.

“The consensus Berlusconi managed to obtain back then in such a short period was truly unpredictable,” says to the author University of Milan sociologist Nando Dalla Chiesa, whose father was killed by the Cosa Nostra in 1982. “Surprising given the fact that he himself belonged to the very same system that Mani Pulite wiped out. Somehow he was able to emerge clean out of it and sell himself as innovator.”

Courts have already ruled that Dell’Utri and the dons were pulling strings behind the scenes. In a separate trial, judges ruled in March that Dell’Utri promised the mob that Berlusconi’s government would do its bidding in exchange for the Cosa Nostra’s political support.

“There is evidence that Dell’Utri promised Mafia advantages in the political sphere for which, in return, the Mafia itself would vote for Forza Italia in the [March 1994] elections,” the court of appeal said. It sentenced Dell’Utri to a seven-year jail term.

Published on the Global Post.

Prosecutors say although the negotiations between the Mafia and the government were already underway before Berlusconi took power, a deal could be reached only after his election.

Prosecutors say an uneasy peace descended on Italy on the basis of the agreement. As the trial continues, prosecutors have already reportedly faced threats — in a country where criminal groups have killed 24 prosecutors.

Also facing tricky questions over possible dirty deals with the mob is President Giorgio Napolitano who is among hundreds of witnesses expected to be called for his presumed knowledge of facts pertaining to the deal.

Despite the trial’s high profile, analysts believe it will have little effect whatever its ruling on a political system that’s too corrupt to take action.

“If the verdict confirms the prosecutors’ theory, there will be no repercussions — at least not on a political level,” says the University of Milan’s Dalla Chiesa. “There would be big headlines in all the major newspapers but nothing more.”

This article was published on the Global Post on June 10 2013.